I am a very conservative in the choice of procedures that I offer to my patients. I would never describe myself as a 'pioneering' surgeon. By definition, these surgeons like to think of themselves as being at the forefront - leading the rest of us. But there is one drawback with being an explorer into the unknown. You don't really know what the future will hold, and you don't know whether your pioneering idea is safe or dare I say it... unsafe. This is all very well for explorers putting their own safety at risk (think of Livingstone's adventures in discovering deepest Africa) but there is one drawback with being a surgical pioneer. You may be putting your reputation on the line, and this is fine, but unfortunately, if your ideas are wrong then you are opening up risks to your patients - and we all know the ethics of our profession. The most important lesson that all doctors learn is the Hippocratic oath, including his most precious of quotes - "Do no harm." This should be a surgeon's main priority.

"Livingstone, I presume?"

It is for this reason that I have been a relatively late uptaker of the new procedure on the block in bariatric surgery - the mini-gastric bypass. I have seen new devices and procedures come and go on a regular basis. I attend our World Congresses and read the current literature in the field of weight loss surgery (and other areas that I am interested in such as reflux) and there is a recurring theme with these new 'breakthroughs'.

A single, or group, of pioneering surgeons will present the amazing results of their new operation and there will be a real initial interest. The next year a vanguard of 'early adaptor' surgeons will also publish promising data on the new operation. Then the following year, just as you are expecting even more interest in the new breakthrough, all goes quiet. Surgeons are not publishing their promising results anymore and in fact nothing is really published, or presented. You hear on the grapevine, through corridor conversations that in fact the new procedure is not as safe or as effective as the pioneers had hoped.

One of the real weaknesses in the publication of research in the surgical field is a concept called 'publication bias'. Surgeons with poor results, or dare I saw it, serious life threatening complications to their patients, are reluctant to raise their heads above the parapet for fear of their reputations being shot down. This is why, when a new procedure goes out of favour it just goes silent - nothing is published. You then presume that your initial instincts regarding the safety or effectiveness of the new procedure where probably correct.

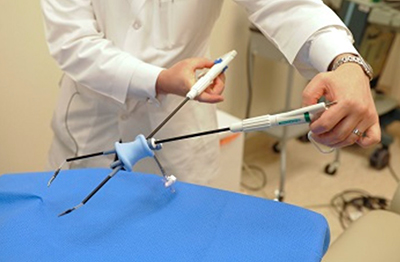

One of the prime recent example of this was the brief craze for 'Single incision laparoscopic surgery' (SILS). This involved performing keyhole surgery not through 3, or 4, small incisions but through a single 15mm incision (normally hidden in the umbilicus). The surgery suddenly became really difficult as you had a worse view and poorer control of instruments. The pioneers assured us that it was safe but after trying it out on a mechanical surgical simulator at one of our conferences I just could not understand this. It seemed that you were making simple operations much more difficult and dangerous just for the sake of a very minor cosmetic advantage.

SILS - briefly 'a new breakthrough', but very awkward and more dangerous than traditional laparoscopic surgery.

Needless to say, my concerns were correct. But I was not informed of this by a series of publications telling us all how these operations were indeed more dangerous than what we had been doing for years. No, there were no publications, no newspaper headline about how our surgical pioneers got it wrong... no-one published their complications or bad results - it just went quiet.

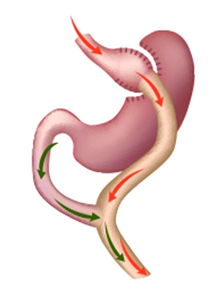

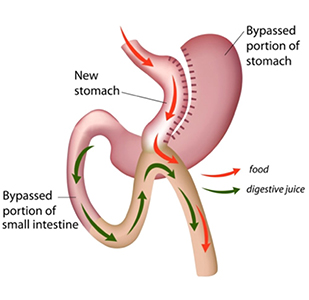

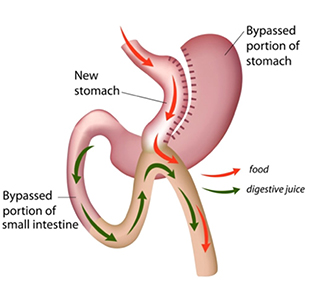

With the new mini-gastric bypass procedure I was similarly concerned about this so-called improvement to the traditional gastric bypass that we all knew was safe and effective. The rationale for the new procedure seemed, to me, to be that it was a shortcut. Making life simpler for surgeons. Instead of performing 2 surgical joins, as had been the case with the traditional bypass, this new procedure suggested that you could perform a gastric bypass with only one surgical join. In fact, the pioneers of the mini-gastric bypass were telling us that not only was the operation simpler and faster to perform, but also that it was safer and... more effective. It seemed too good to be true and I was concerned that it may be an operation that surgeons who were not that technically gifted were performing as a short cut - to save time and stress.

The difference between the traditional and the mini-gastric bypass - one join instead of two.

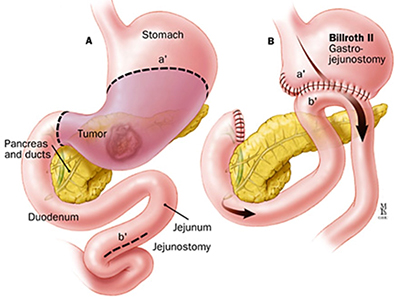

On top of my natural cynicism for new procedures was a serious concern about the long-term safety of the mini-gastric bypass. A large body of surgeons had suggested that the mini-gastric bypass was like an old operation that used to be performed for people who had gastric ulcers. This operation was called the Billroth II and many thousands of them had been carried out before drug treatment for ulcers became more effective in the 1970s.

The worry was that some long term follow up studies suggested that people who had undergone the Billroth II operation had a slightly increased risk of gastric cancer developing in their future lives. The suggestion was that this was caused by bile from the single join refluxing into the stomach and exposing the stomach cells to malignant changes. The surgeons were concerned that the 'plumbing' for the Billroth II and the mini-gastric bypass was similar (see diagrams).

The Billroth II procedure and the mini-gastric bypass both join a loop of bowel directory to a stomach pouch.

As the years passed these concerns grew and at every congress there where major discussions and debates about the potential future risks of the mini-gastric bypass. But one thing was different with this procedure compared to previous new developments - it was not going away... year after year the popularity seemed to be growing with more and more surgeons worldwide publishing really promising outcomes - both for weight loss (which did indeed seem to be even better than the traditional gastric bypass) but also short term safety (less bleeding and leakage). But the real concern remained that we may have been popularising a new operation that could put patients at long-term risk of developing gastric cancer.

OK, so here is a summary of the outcome of the multitude of discussions and disagreements amongst surgeons of the last few years.

There is agreement that some studies did indeed show a marginal increase in the risk of gastric cancer after the Billroth II procedure (20 years after surgery). However, the risk was marginal and several other long-term follow-up studies did not show any increased risk. But, even if there was indeed a small increased risk of gastric cancer developing after Billroth II this did not automatically mean that the operation itself caused the risk. What is now accepted is that the patients who underwent Billroth II procedures were already at an increased risk.

Billroth II was performed for intractable gastric ulceration. Gastric ulcers are now known to be commonly caused by a bacteria that inhabits the stomach. The bug, called H. Pylori (helicobacter pylori), also confers another risk - a marginal increase in the risk of gastric cancer. So here we have the answer to our debates and discussions - the Billroth II operation itself did not cause the increased risk, but the patients who underwent it were already, because they had gastric ulcers, at increased risk because they were more likely to harbour H pylori.

Therefore, it was concluded that if the Billroth II operation does not confer any extra risk of gastric cancer developing then certainly the mini-gastric bypass does not. The theory that 'the pluming is similar' therefore there must be a similar risk are negated by our discovery of H. pylori as the culprit, and not the plumbing.

So, now that we are reassured about the long-term safety of the mini-gastric bypass what about its effectiveness? Are the early promising results of the pioneers (which are often misleading and biased) really true?

We now have robust, long term results, from many different centres around the world, and from many thousands of patients, over many years, which all seem to point in one direction. Yes, this new operation - seen by many, including myself initially, as a short-cut operation does indeed seem to be an improvement on the traditional (Roux-en-Y) gastric bypass. The risk of bleeding and leakage is less (because there is only one join instead of two), the operation time is less for this reason as well.

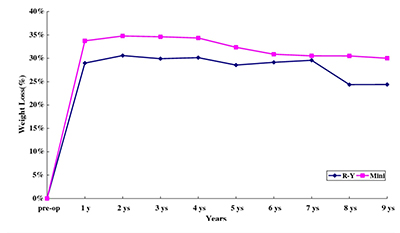

Mini-gastric bypass v traditional gastric bypass 9 year follow up.

Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y vs. mini-gastric bypass for the treatment of morbid obesity: a 10-yearexperience. Lee WJ et al. Obes Surg 2012. 22(12): 1827-34

But, not only is it safer and faster. Over 5-year follow up there is a consistent trend in significantly better weight loss after the mini-gastric bypass compared to the traditional one; by about 10% more excess weight loss. In addition, the resolution of type 2 diabetes seems to be even more pronounced with the 'mini '.

My conclusion; the mini-gastric bypass is a much more powerful operation than the roux-en-y gastric bypass. The term 'mini' is actually a misnomer - yes, it is a shorter and simpler procedure to perform, but it is by no means 'mini' as far as its effectiveness is concerned compared to its more established older brother - it's more like a macro-bypass.

Many surgeons now prefer to name the mini-gastric bypass as either the 'omega-loop bypass' or the 'single-anastomosis gastric bypass ' to prevent the perception that it is a gastric bypass-lite.

There are some instances where the traditional gastric bypass remains a better option than the mini-gastric bypass. The most common one is in patients who have bad acid reflux as well as obesity (and/or diabetes). We know that the traditional gastric bypass cures reflux (gastroesophageal reflux disease) whereas the mini-gastric bypass may make it worse.

My conclusion to our question? Yes, in many instances the new mini-gastric bypass does indeed seem to be an improvement on the traditional gold-standard roux-en-y gastric bypass procedure.